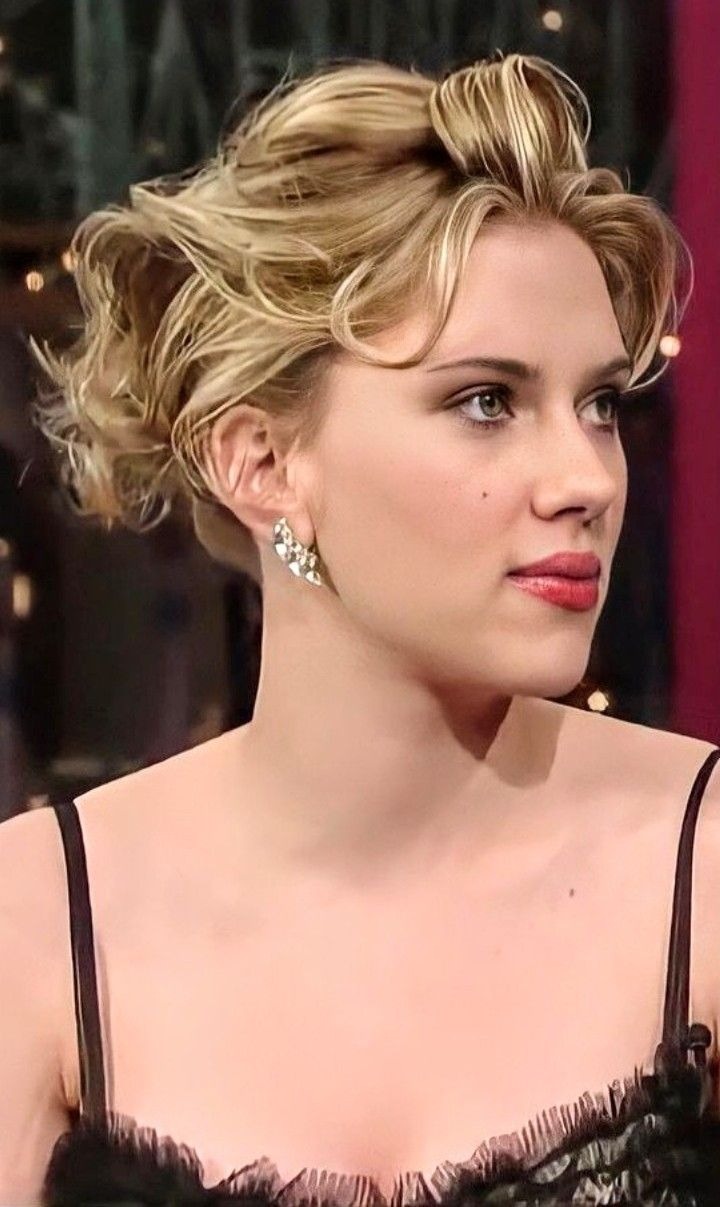

Seven years later, she is the obvious choice once again. This time, even Sєxier.

Four-fifty on a Thursday afternoon, deep in a shadowy bar at a H๏τel called the Nomad, downtown Manhattan, and Scarlett Johansson actually wants to write. I give her a little H๏τel pad, maybe four-by-six, which she grabs in her small, ringless fingers. She takes my pen eagerly.

“What do you want me to write?” she says. She will write what I tell her, she says.

I don’t know. “Don’t you have a little pᴀssage memorized?” I ask. “A little Shakespeare, maybe? ‘Oh, for a muse of fire,’ something like that?”

She clicks her tongue. “I think it should be neutral,” she says, shaking her head. “Shouldn’t involve any acting. I’m afraid I’ll emphasize the Oh or something.” As she thinks, she purses her lips, looks down, casting a little furtive charm. This one. She came in here — and this place is hung with velvet curtains and underlit by 40-watt bulbs; it’s seriously dark — with her sunglᴀsses on, walked six feet in front of me, at her publicist’s side, in her gray cotton tracksuit, half pointing at tables that might work for her. All movie star up in here. And I didn’t look at her ᴀss. I don’t know that she wanted me to. Probably not. Surely not. In any case, I didn’t.

She bites the inside of her cheek when she thinks. There is an extremely large platter of cut vegetables on the table. “Crudités.” I say it out loud, a word no one used ten years ago.

“My God,” she says when it arrives. “So many vegetables.”

Her voice is a raspy frequency in the air. Legitimately as pertinent and defining a component of her physical makeup as her lips, her cheekbones, her legs. When you’re with her, you feel that voice. This bar is loud with cocktail hour, but the matter of her voice, the fact of it, hangs in the air even so — always a little sandy, somehow broken down, as if she’d been singing all day. Whether she breathes right or projects well I do not know, but her voice cuts the murmuring clatter of forks against small plates, ice spun in highballs. You can hear it no matter what.

“I wish I could write a parable,” she says. “Or maybe just an adage. I could write that one where I never know what the hell it means. Well, I guess if I thought about it — I mean, I have thought about it, of course, and figured it out. But it eludes me the first time I hear it. Every time. It’s not logical. At first, I mean.”

“Like ‘A sтιтch in time saves nine?’ I never get that one.”

“Exactly,” she says. “But it’s about birds. ‘A bird in the bush.’ Or…”

“Oh, yeah.”

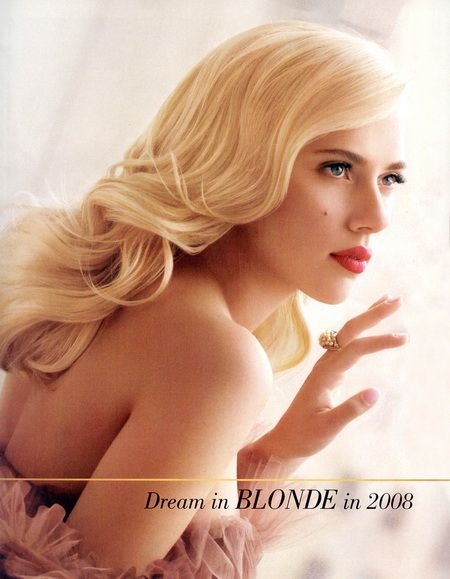

Media Platforms Design Team

—Scarlett Johansson

So these are the words she writes: A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. Twice. Once in cursive. Once printed. Then she slides the pad to me and says, “Now you do it.” And so I take the pen. A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, after all.

“Come on,” she says.

“Okay,” I say. “But you’re making me nervous.”

I write it once. “Now print it,” she says. And, of course, I screw that up. So my printed line reads A BIRD IN THE HAND IS WORTH TWO IN THE BIRD.

Scarlett Johansson clucks into the air. “That’s gotta be bad for the bird,” she says. Me, I want to start it all over again. “No, no, it’s fine,” she reᴀssures me. “Just give it to them that way.” She bites a thin hook of sweet orange pepper. “See what the words tell you.”

We’re creating a handwriting sample. Scarlett offers hers for me to take to a graphologist for an analysis of character. You could say she was eager, a movie star all the way, uncowered and free. When she’s like this, willing — wanting even — to give in to harebrained plots, you really feel like you’re talking to a bombshell, because bombshells are fun. To her, it sounds like fun to have a stranger deconstruct her penmanship in the sidebar of a magazine article. It’s part of a search for truth, after all. Not exactly bungee jumping, but Scarlett is brave like that. She’s not one of those who pine for the privacy lost to celebrity, nor does she tell teary stories of some paparazzo who stalked her in the doorway of a cupcake shop. Scarlett just plain operates in the world, which can make her seem a little chilly at first, even sour.

She’s only twenty-eight. She’s been at it long enough to have done most of it before. Critical success, commercial success, action movie, its sequel and re-sequel. Lost in Translation to Vicky Cristina Barcelona to the various iterations of the Avengers. She’s now been the Sєxiest Woman Alive twice — well earned, too. But what do they say about impressions?

The first of her: She seems not to care, to be bored, aloof. But that’s as if drawn only from looking at pictures and not reading the text. Truth is, Scarlett is a politically astute, card-playing, magic-loving smart-ᴀss, fairly generous in her time and attentions, a woman who will share her sandwich, a woman who likes horsing around in a bar on a muggy afternoon, a platter of hand-cut vegetables at the ready.

This year, Scarlett says, has been the busiest of her life. One movie released, two more coming out in the next five months, and two more in production. She finished a full run of a Broadway revival of Cat on a H๏τ Tin Roof in March. In the movie she has out right now, Don Jon, she plays the H๏τ, manipulative girlfriend of a porn addict. She makes a hootchie girl elegant, offering ascendant beauty in every scene. Hers is an unstressed beauty, which may be why her look is so mutable, more slender than buxom and fleshy. Her next movie is Under the Skin, a horror film in which she plays a flesh-tearing supernatural wandering across Scotland.

In this bar today, she does not look like that horny Catholic in Don Jon for a dozen reasons you already know: She’s wiped out from the pH๏τo shoot, wearing no makeup, different shoes, different bra, and so on.

“I’m exhausted and this is my last day in the world,” she says, sunglᴀsses off now. “This is the last day, and this is the last piece of work. Then I’m taking a month-long vacation. But I’m not going anywhere, which just makes it more of a staycation. There’s luxury in being near home. When you spend a lot of time, like I do, just standing around and waiting, or being moved from place to place, every minute gets consumed by something someone else has set up for you. And it’s not like I’m always in a beautiful place wearing something gorgeous. I’ve stood around bogs wearing half a million dollars’ worth of jewelry, up to my knees in the rot, thinking how much more or less the place smelled like a sewer than it did the day before. And that is not what you’d call a problem exactly; it just wears you out. What I want to do right now is sleep late, read the paper. I’ve come to see that there’s something pretty great about having two hours to read.”

Why accept the тιтle Sєxiest Woman Alive if everything is so busy just now?

Here, she shrugs. “I’m the only woman to win it twice, right?” she says.

She is correct.

“You know, I gotta hustle. I’m a twenty-eight-year-old woman in the movie business, right?” she says. “Pretty soon the roles you’re offered all become mothers. Then they just sort of stop. I have to hedge against that with work—theater, producing, this thing with Esquire.”

Then, as if she hears herself, she looks straight at me and says: “Sounds pretty bloodless, I guess.”

She’ll spend her vacation on the beach in the Hamptons, in a house she rents with friends. “It’s a contemporary house, with a modern Swedish slant.” For whatever reason—my own prejudices, a tone I mistakenly pick up on in her voice, beach houses I have known—I ᴀssume she’s saying, the way people do when they rent, that the furniture sucks but it’s fine because the water’s right outside.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

And here I say, too casually, “Swedish? Like what, like Ikea and that sнιт?”

She smiles wryly and speaks softly, unruffled and clear. “No,” she says. “Not like Ikea.”

Pretty soon, we’ve sat there for more than an hour. The conversation is fully shared by the both of us then. She’s asking me things as if she knows me, which is, of course, about as true in reverse as well. But she is, at root, a curious person. “What are you doing with your summer?” she says to me at one point.

“I don’t know,” I tell her. “We just moved to a smaller house. I’m renting. There’s a guy two doors down from me who has four goats. Right in town. Goats.”

“Goats are pretty sketchy,” she says. “You have to watch out.”

I tell her: “Not these goats. I like all four of them.”

“Pigs are actually okay. Horses and cows — all good.”

“I don’t have much experience with those animals.”

“It could be worse. He could have chickens.”

“True.”

“Chickens scare me,” she says. “I don’t like them. They seem a little floppy or something.”

“Floppy?”

“They’re vicious. I had heard the term ‘pecking order,’ but I had no idea what it really meant until I got to see a large group of chickens in a coop. That is some ugly business.”

“They need dust baths,” I tell her. “Every day.”

“Kind of nasty, right?”

“My impression was this keeps them clean.”

“Geese are mean,” she says. “You gotta step a long way off from a goose.”

A moment goes by, then two, when, just like that, she claps her hands. “Welp, that’s the whole barnyard then. We got that covered. What do you do with your days?”

“Wait,” I say. “What do you do with your days?”

She holds her hands out, palms up, and smiles into a what-do-you-think shrug.

I get that. I’ve got it by then, anyway. So I say, “I get up early, go to the coffee shop to play cards for a while. And then…”

“I love cards,” she says. “Are you playing poker?”

“Cribbage,” I tell her. “It’s a good game. Fast. A lot of counting.”

“But is it frantic? Everybody slapping cards down this way and that?”

“No. Just fast. And quiet. You just go round the board, then round again.”

“Sounds meditative,” she says. She puts a finger to her chin. “That would be very pleasant, I think, to start the day by playing cards.”

I offer what wisdom I’ve taken from the habit: “It clears my head, makes me more rational.”

“I don’t really aspire to being rational. I’m more attracted to the irrational,” she says. “There’s no such thing as total rationality. That’s something I’ve realized lately.”

“You saying I shouldn’t play cards?”

“No,” she says. “Just that you’re never free of the irrational, so you might as well—” She pauses there. I think I must be looking at her too hard. “Oh, I don’t know,” she says, stopping before picking up again. “Like, it’s okay to be jealous, for example, which people think is irrational. To let yourself care that much that the emotion might hurt you a little.”

“So it’s okay, even if you have no reason to be jealous?” I ask.

“Look, I’m with a Frenchman. I think jealousy comes with the territory. But I’d rather be with someone who’s a little jealous than someone who’s never jealous. There’s something a little ᴅᴇᴀᴅ fish about them. A little bit depressing. It may not make sense, but you need to feel it a little. I know, irrational, right?”

She sips water and thinks. “I didn’t think I was a jealous person,” she says, “until I started dating my current, my one-and-only. I think maybe in the past I didn’t have the same kind of investment. Not that I liked my partner less, I just wasn’t capable of it or caring that much.”

Evening is coming on, and the vegetables have become soggy and picked-at. Eventually Scarlett stands, shakes my hand. Tugs on her little gray sweat jacket. Then she says in the unmistakable rasp of her voice, with what sounds like sincerity, “Too bad it’s not two weeks from now. You could have come to see me on Long Island. We could have had a lobster roll and played some cribbage.”

I decide to take that as an offer. I drive out to Long Island — Amagansett, at the eastern end — and we meet at a lobster shack. Eat a lobster roll and play cribbage. This is a day in the middle of the aforementioned staycation, her thirty days of time off after seven months of work without cease.

“Hey.”

I had forgotten about the voice. Strong voice. In any space, it seems Scarlett Johansson is always closer than other women, even though right now she’s sitting in a way-over-there chair on the other side of the glᴀss table, taking in the rollicking lunch crowd over my shoulder, with her back to the wall. A beautiful woman, luminously watching a cloudy, unilluminated afternoon from behind the clamp of some large, large sunglᴀsses.

The sunglᴀsses are big enough that I realize I haven’t really gotten a look at her. And then, for some reason, I’m suddenly about to ask her to take them off so I can see her face. I’m about to tell her what I want, making it a demand, an ᴀssertion, rather than a request. So dumb, so overly familiar, so wildly inappropriate that I don’t have time to think of better things to say. So I choke back the words. Inexplicably I say “Sunglᴀsses,” just that, as if making a note in the afternoon air between us.

“What’d you say?” she says.

And like a moron, I can muster only this: “Do you like wearing sunglᴀsses?” To which I add: “I guess you’d have to.” Brilliant.

“Oh,” she says, emphasizing the Oh before she looks away. She lifts and drops the glᴀsses in place on the bridge of her nose. “I do. I have sensitive eyes. The light really gets me.” She looks out to the sea, across the road and over a dune, as if testing things. I believe she sighed then, but I can’t really say. What she said: “There’s that. And, well, you know. I have to live behind them, because I’m a movie star.” She lifts an eyebrow, acknowledging the simple truth of it. It’s her trademark I-dare-you glance. Then, with some lip-pursing and a calculated shrug, she pinches her eye and mutters, just like some old guy making sandwiches in his kitchen apron, “Whatta you gonna do?”

Eventually she asks: “Hey, what about the handwriting sample?” She’s H๏τ on this, genuinely interested. I give her the bad news: Apparently, in the world of graphology, the eleven words that compose Scarlett’s chosen adage make for an unthinkably short sample. No graphologist can work with so few words, no matter how much money I offer. Most of them want a minimum of 250 words on a blank page, plus a signature. Seven of them, dredged from the Internet, turned me down. “You got nothing on this girl,” one of them told me over the phone. “You’re saying she wrote this on lined paper? That itself nullifies the sample. And on a small pad? That’s no good, either. Did you get her autograph?” Of course not. “Then you got nothing. This is a science, you know. You can’t ask an astrologer to work unless he can see the stars.” Which is really not true. I ended up feeding it into an automated online graphology site, which spat back some universal vagueness about how she’s optimistic but sometimes questions things.

Scarlett looks slightly disappointed, but perks right up again and moves on. “How goes the cribbage?”

At which point I break out a deck of cards and the board grabbed from my game shelf the day before.

“Oh, Milton Bradley!” she says, as if she were seeing an old friend through a car window. She picks it up pretty quickly, and not long after going over the rules we’re playing a live game. Still, it’s complicated. Second hand in, she raises her eyebrow, exasperated with her luck. “So you mean you guys play this — go round and round, throw cards down — and have normal everyday conversation? I thought you said it wasn’t frantic.”

It isn’t, not in my experience. You can talk during cribbage. Once she understands the game — even before that, really — she rambles. She can talk. Really talk. She is the Sєxiest rambler alive. Her words: lazy, light, no particular rush. Like any game in any gin joint, breakfast place, or lobster shack, it’s mostly chit-chat, general kidding around. No matter. She is to be listened to. Until the last hand, her voice sounds, as always, like she just woke up, wary, but delighted by the game she’s about to play.